Addiction to Perfection is a book my teacher Marion Woodman wrote in 1982. It was the first book that introduced me to her work. When I read it, I thought I understood who the perfectionist is in me. And I thought I understood how she got in my way.

It wasn’t until this past week when I gifted myself five days to paint that I became acquainted with the bully side of perfectionism. I am using the word “bully” because perfectionism has many colors. It’s not just about wanting things to look, feel, and be perfect. It’s also about the lack of tolerance and patience for the human experience, which is anything but perfect. When we confront the part of us that is so unforgiving, we have to face what is underneath that voice that won’t give us a break.

I think in my case that voice is some imaginary person I have created in my unconscious mind. She is able to be good at everything she does. She doesn’t need to learn slowly and doesn’t recognize the amount of courage it requires to learn something new.

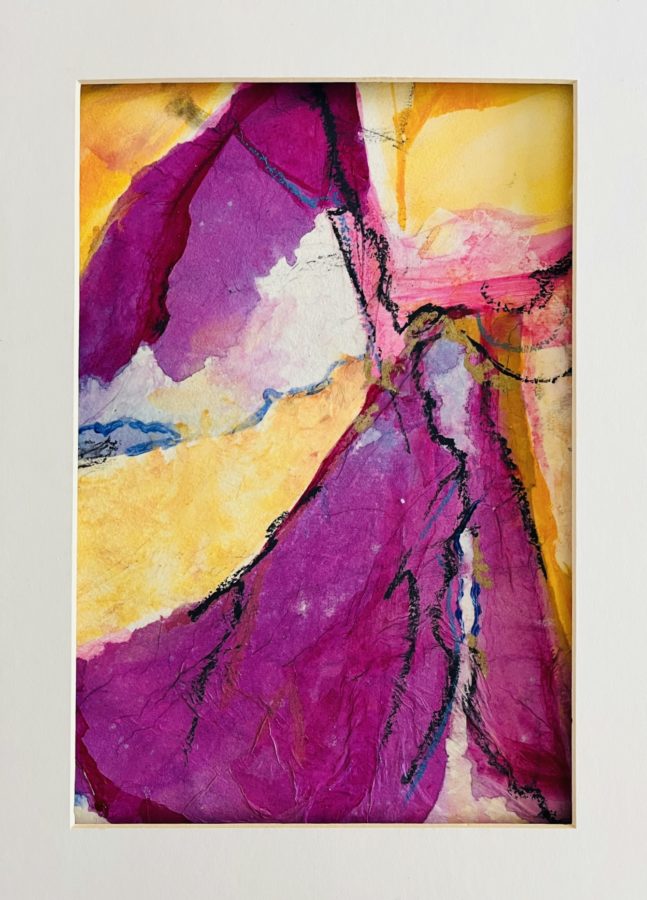

So to be specific, in this painting retreat, I was enjoying the part of me who knows how to play, and I was enjoying how my intuition and energy flowed on the canvas, but I had very little ability to self-critique my work without going overboard into annihilating and destructive thoughts about the areas in which I have much to learn.

What excites me about painting is the joy of putting color and line on a canvas. I haven’t been doing it long enough to develop much technical skill, and that’s fine, but it means that I need to learn a lot about what is missing from my work and what will make it stronger and how to find the right team of teachers to help me get where I want to go.

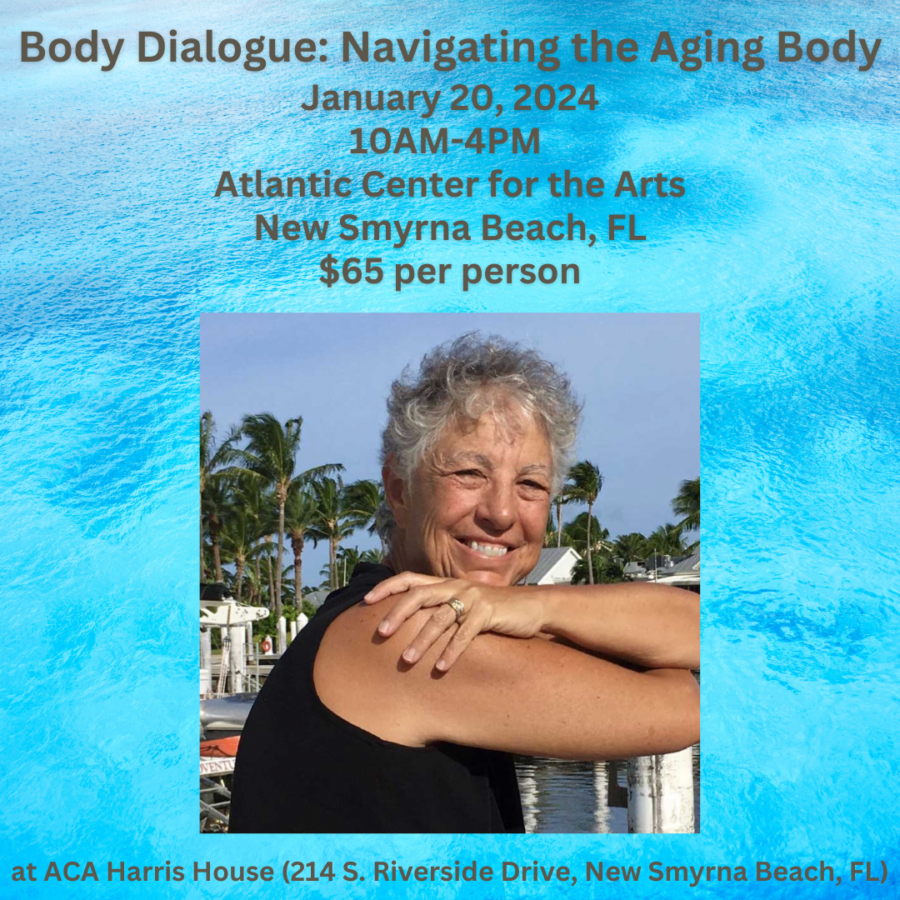

I do have mastery around the work I’ve been doing for 40 years as a bodyworker. I started in 1979, and I knew it was going to take me a long time to get to a place of mastery. Even now, although I feel masterful in my work, the joy is in the process of discovering more and more every day.

The addict who needs perfection allows no room for mistakes, which in fact is part of the creative process. To quote the writer Raymond Carver, “You have to be able to recognize a gift when it comes, and mistakes are a part of it. Sometimes mistakes are the best thing that can happen to you in your work.”

I’ve found that addiction to perfection is connected with shame. Perfectionism goes hand in hand with shame. If you examine something you feel ashamed about, beneath the surface is often an expectation that is a close cousin to perfectionism.

Imagine, for instance, that you are in a relationship with someone who is really important to you and you do something that is truly clumsy and does not take into consideration the other person’s feelings.

At first glance, it might not appear to be specifically connected to perfectionism, but to not accept that relationships are about human beings navigating this imperfect world that puts so many pressures not only on ourselves but on the relationship itself.

That drive to not hurt another person, to not be insensitive or step on another’s toes, is perfectly understandable, but relationships are often messy, and it’s in the mess that we learn to trust one another.

So I ask myself these days, when so much disruption and disintegration is happening on the world’s stage, how can we be more gentle with ourselves and the ones we are closest to.

In looking back on my recent experience of painting with a group of professional artists, for whom their craft and their passion continues to excite them, I have realized that I don’t have to know everything or be good at everything. I don’t have to have a finished work of art every time I put my paintbrush to the canvas.

In fact, the reason I am intrigued by this process is that I don’t really know what I am doing and I am excited by that. Now, I have to stay with the excitement and not be frustrated that the “success” of the product is not as readily accessible as I might want. And maybe my concept of success has to be reevaluated. I invite you to think about what makes you feel alive today and engages you fully. That was the success of my week painting. For one week, the only thing I really cared about was color, line, light, and process, and that made it a successful week. I hope you can relate to this and, if so, feel free to get in touch and tell me how your creative journey is serving you right now.